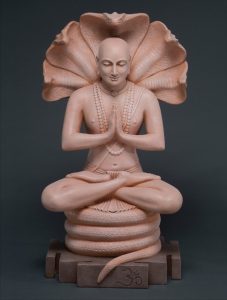

The sage Patanjali, author of the yoga sutras

Modern postural yoga is but one aspect of a total system of self understanding and self-compassion.

In my last post, I briefly surveyed the first of the eight limbs in the ashtanga yoga system, the yamas. Here, I’ll do the same with the niyamas, the five observances of the self, again drawing on both BKS Iyengar’s and Chip Hartranft’s writings to help illuminate their meanings and applications.

- Saucha – purification. We can understand saucha best as modern Western practitioners of yoga if we take the application of “purification” simply and literally. Many modern interpretations of the eight limbs advocate saucha as cleanliness of body and mind. Personal hygiene and proper diet (ultimately culminating in vegetarianism), along with regular practice of the next two limbs, asana (posture) and pranayama (breath control), prepare one for the discipline required for the next four limbs. Iyengar further advocates a clean and clutter-free space for practice (which is why you often see shoes left outside of yoga classes, as well as Hindu temples). The concept also extends to purity of mind, so cleansing the mind of “impure thoughts,” which I will leave in quotation marks for you to interpret as you see fit! (But then also see my note* below.)

- Santosha – contentment. A result of disciplined practice of the yamas and of saucha. Iyengar says, “the yogi feels the lack of nothing and so he is naturally content.” Our practice is intended to culminate in a letting go of external attachments as sources of our personal happiness. When we realize we already have everything we need within, contentment arises. Hartranft interprets this experience as joy.

- Tapas – heat. The fire of committed discipline in one’s practice (of yoga). Think of our third chakra, manipura, the solar plexus and heated center of our will. When we’re healthy in body and mind, naturally there arises the concentrated effort required to understanding the self and seeing our connection with the life force energy that connects everything in its radiance. I particularly love the way Hartranft sees tapas: “Every time a distracting impulse is noted but not obeyed, the body-mind sees through and beyond it, gaining energy and inching closer to discriminating awareness.”

- Svadhyaya – self study. Iyengar, sounding very Joseph Campbell: “The person practicing svadhyaya reads his own book of life, at the same time that he writes and revises it.” In one sense, self-study means literally studying: the philosophical texts or “wisdom teachings” (Hartranft), but also applying them to practice in service, devotion and meditation. What’s on your bookshelves? As a devoted student of Jungian and archetypal psychologies and their many similarities and overlap with yoga philosophy, I do a lot reading related to understanding myself/the self. But I also record my dreams, I take them up in analysis and continue to mine them for clues to my own individuation through writing, art and meditation.

- Ishvara-pranidhana – surrender to God. Literally, from Patanjali’s text: “From submission to God comes the perfection of samadhi” (samadhi is the 8th limb of the ashtanga system; experience of pure awareness that we are one with God). Again, in our practice of yoga as modern Westerns, we can interpret this sutra not merely to more comfortably fit our own beliefs, but more to understand the nuance around what we mean by “God.” Here is an example of the many conundrums that define Hinduism as well as the modern practice of Yoga. We want more people to experience the benefits of practice, but we don’t want to step on anyone’s religious beliefs, so we claim that “yoga is not a religion. It’s a science. It’s a philosophy. It’s a psychology.” (Or as Iyengar crowns Yoga, “the science of religion.”) I and many of the authors and commentators on the sutras believe all of these things. But here in sutra 2.45 is the word for “god” (or “lord”): ishvara. We put our palms together in prayer position, we honor the divine in one another in “namaste.” For each of us, these are possibly deeply personal gestures we bring to our practice, so it’s worth a few extra words to further stimulate reflection. Hartranft interprets “pranidhana” as “application” or “alignment,” as one’s “orientation” to the goal of achieving samadhi. Additionally, he allows for the idea of pranidhana as “surrender” as that which we “make in every moment – to let nature unfold exactly as it will, without our attachment or aversion – thereby entering the perspective of pure awareness.” Sidestepping? Possibly. But allowing for multiple interpretations allows each of us in our personal practice to define devotion, commitment – the intensity of our practice – in a way that makes personal ideological sense. It doesn’t bar anyone from the practice of yoga who chooses not to practice on strict, Hindu-theistic grounds. And this discrimination comes from self-study, from svadhyaya.

To enhance the experience of your practice, whether on the mat with me in session, or on your own (off the mat or on), consider these deeper teachings of yoga summarized here and in the previous post. See how they make sense as integrated with your santosha, your intention for your practice, or as part of your daily meditation or regular prayer practice. From there, begin to notice how the practices (multiple now: yamas/niyamas, asana, pranayama) begin to infiltrate your awareness of your other daily activities. You’re on the path of the true yogin.

Hartranft, Chip. 2003. The Yoga Sutra of Patanjali. Shambhala Classics. Boston.

Iyengar, B.K.S. 1979 (1966). Light on Yoga: Yoga Dipika. Schocken Books. New York.

(*A strict, historical reading of the commentaries on saucha refer almost exclusively to understanding the body as offensive; as habituated and biologically driven to what we have learned to regard as “digusting.” As clean as we can make our bodies, there is no such thing as a 100% purified body, outside or inside. There is always something unclean, somewhere. It follows that if one understands the body in this light, one will lose the attraction not only to one’s own, but to other bodies as objects of erotic desire. And when we lose desire, we come closer to santosha, contentment. For more see Edwin F. Bryant’s The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. 2009. North Point Press. New York.)