I remember when I learned that yoga was about more than postures. It was in my early days as a yoga student, but probably a year or so into attending classes at Dallas’ Iyengar yoga studio. I attended a 6-week beginner series, and then I dutifully attended it again, at the suggestion of my teacher. And not for any remedial need; the suggestion was given to everyone as a way to really cement the first level teachings, Iyengar yoga being a strictly hierarchical practice. If you didn’t feel completely ready to proceed to level 2, take the 6-week beginner series a second time and move through any vulnerabilities. That was the message I chose to receive anyway.

“Light on Yoga” is B.K.S. Iyengar’s book on the practice of yoga. First published in 1966, it contains the now classic black and white photos of Mr. Iyengar in every yoga pose; and in the “fullest expression” of every yoga pose, with none of the ubiquitous props he would become known for, no modifications. I understand the whole project nearly did him in.

But in the pages before the photos and descriptions of the poses, there is Iyengar’s treatise on yoga as practiced by those under the tutelage of a guru or teacher. Here is where I first learned about the philosophy underlying the practice of postures and breathing practices (a completely separate practice and instruction under the Iyengar system). Patanjali’s philosophy of ethics, including the yamas and niyamas, often translated as “observances” and “restraints,” establishes the ground on which the physical practices rest. And a practice that talked about meditation and the evolving relationship to self and ego as the cornerstone of what I was attempting in postural yoga was something I wanted to know more about.

But I didn’t really get more of that by going to yoga classes. There was always the opening mantra, or “hymn to Patanjali,” chanted in Sanskrit that one was expected to simply follow and learn by repetition. I don’t recall anyone ever offering a translation. Workshops offered deeper dives into pranayama or posture work with more advanced teachers, but nothing particularly heavy on the metaphysics. I kept on with classes in any case and in another year or so came across Stephen Cope’s book (I’m a bit of a bookie) “Yoga and the Quest for a True Self.” Cope is a psychotherapist and yoga practitioner who contextualized the ethics and psychological project of a yoga practice for 21st century westerners like myself, who were still a little mystified by what was often mentioned in passing during mainstream group yoga classes. His approach made sense to me. Westerners are wired for a psychological understanding of what a yoga practice offers.

This realization, and the fruit of what I took from Stephen’s Cope’s work led me to revisit my interest Jungian and post-Jungian psychology and theory. In this exploration I tried to marry what I understood about Jung’s process of “individuation” and yoga. Judith Harris’ book “Jung and Yoga: The Psyche-Body Connection,” for example, is a clinical study and application of Jungian theory to the experience of trauma as it manifested in a particular patient’s chronic physical symptoms.

This led me to the study of somatics, and teachers who were integrating somatics, body mapping and similar modalities into their yoga teaching. I took somatic yoga classes with Carla Weaver at the Dallas Yoga Center, and yoga and trauma workshops with psychotherapists Amy Jones and Tzivia Stein-Barrett. James Conger’s “The Body in Recovery: Somatic Psychology and The Self” and Besel Van Der Kolk’s “The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and Body in the Healing of Trauma” followed.

Two things led me to seek opportunities to bring the benefits of trauma informed yoga to veterans: 1) the realization that there is a massive disconnect between federal resources available to help treat veterans suffering with the symptoms of PTSD, and those resources actually making it to veterans who needed them. The bureaucratic red tape was probably exacerbating the rate of soldier suicide. The second thing was something that hit a little closer to home. Micah Xavier Johnson opened fire on police officers from a parking garage in downtown Dallas during a peaceful Black Lives Matter march, killing four of them, and wounding two others. Johnson was an Afghan Army Reserve soldier who’d returned home disillusioned, depressed, anxious, prone to panic attacks and flashbacks. He was treated by the VA but not formally diagnosed with PTSD, though his record indicated he showed symptoms of the disorder. He was instead prescribed four different medications to address his symptoms.

There are a few national programs, like Warriors at Ease and Veterans Yoga Project that offer teacher trainings all over the country and Canada. I kept these on my radar, but I felt an urgency to do something, to find some small way to help in the meantime. I screwed up my courage and walked into the Dallas Vet Center one afternoon on my way to teach a corporate class. I lucked into meeting the counselor on call there, who was already familiar with the mind/body/trauma literature and was incorporating breathing practices into his group meetings. I asked if there might be any interest in my coming to teach a yoga class once a week.

That’s how I started teaching trauma-informed yoga. One of my students at the Vet Center introduced me to the Warrior Spirit Project, a local organization I hadn’t previously known about. Now I’m teaching a weekly trauma-informed chair yoga class and have completed the first level of the 30-hour Warriors At Ease yoga teacher training. Next month I’ll begin teaching an in-person class at El Centro College for student veterans and first responders and their families, the same college where Micah Johnson killed those four police officers, and then was killed himself by police.

What is trauma?

Most dictionaries define trauma as the emotional response we have to an event such as an accident, rape or natural disaster. So two parts to unpack: the event itself, and the emotional response elicited by the event. Let’s look at the second part first. How we respond to terrible events can tell us a lot about our capacity for resiliency. If we get into a car accident say, perhaps are even critically injured – ambulance, hospital, emergency/lifesaving surgery with rehabilitation and physical therapy and all the rest – how might our emotional response to such an event take shape? Physical pain produces either tears or full blown shock. Suddenly there are a lot of factors out of our control. We have to give ourselves over entirely to the care, authority and expertise of others to help us. Will I walk again? How long will it take? Will my life ever be the same? How has my life changed and can I meet that change? Can I bear up?

Traumatic events demand that we bear up if we are to heal and continue on with our lives. And the shape of our response is the key to our survival.

There is another aspect to a traumatic event that requires our attention and understanding as yoga teachers, and that is how the residue of the event itself lives on in our bodies. When I cut my finger with a kitchen knife three years ago, the event would, of course, be noted by medical personnel as a “trauma” for diagnostic purposes. And three years on, though I’m fully healed, I’m not scared of knives, there’s no lingering emotional fear around the incident, but I can still re-live the specific feeling of slicing through my finger, just by recalling it; by thinking about it. The physical sensation lives in my nervous system, in the neurons in my brain. Experiences of the body live in memory.

Let’s look at the second part of the definition that gives examples of the kinds of events that we consider “traumatic”: accident, rape or natural disaster. We’ll add to that the experience of combat and other forms of physical or mental/emotional abuse, as well as racial trauma: the experience of on-going, historical discrimination, perhaps coupled with being victimized by racial violence. There is an emotional component intrinsic to these kinds of events that if not processed or worked through becomes embedded in the body-mind and surfaces in the form of symptoms like those we see in Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Because of the severity of these kinds of events there is often a lag time between the event itself and the time one has on the other side to come to terms with what has happened. Unless one is psychologically prepared to deal with events as they occur (an oftentimes heroic undertaking), we are often left to pick up pieces months or even years after the event.

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder is the name given to describe a collection of symptoms including those involving intrusive memories of the event, avoidance symptoms, negative changes in thinking and mood, and changes in one’s physical and emotional reactions (Mayo Clinic). Examples of these include flashbacks and nightmares, heightened startle reflex, emotional numbing, forgetting details about the event, dissociating from people or places that remind one of the event, anxiety, depression, insomnia and irritability, as well as guilt and shame around one’s role in the event.

What’s happening in the nervous system – what’s happening to the body both under normal circumstances and those of a traumatic event – is both complex and subtle. A well functioning central nervous system (CNS) is a balanced play between the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS). This balance is what governs overall homeostasis in our bodies.

The SNS is typically activated under conditions of stress. Our airways open up, our pupils dilate, our heart rates go up in anticipation of the need to “fight, flight or freeze.” The PNS is activated under conditions of calm, or the absence of stress. Our breath quiets as airways narrow, our pulse slows, and our pupils contract. This is what we know as the “rest and digest” response.

Also important in this scenario is Heart Rate Variability (HRV), and an understanding of the function of the vagus nerve and healthy vagal tone. When our hearts respond as they should – our heart rate goes up when the SNS is activated and slows when the PNS is activated – we have “high” heart rate variability. When the heart can’t respond, or is stuck in either a rapid or low pulse rate regardless of the situation or stressor, we call this “low” HRV. We believe people with high HRV, it stands to reason, are more resilient in times of stress.

The vagus nerve (“wandering” nerve from the Latin) is one of 12 cranial nerves and is part of the PNS. It has both sensory and motor functions and sends information about sight, touch, smell, taste and movement from the body to the brain. It governs circulation, respiration and digestion. This is a “bottom up” function of the nervous system and accounts for as much as 80% of the vagus nerve’s communication. Poor nutrition, poor respiration and cardiovascular issues affect “vagal tone.” Poor vagal tone in turn has an effect on mental and emotional health. Think about how chronic health disorders open the door to depression and anxiety; how when we don’t feel well in our bodies, we can’t “feel” well in our minds. In short, because the vagus nerve drives most of the major bodily functions vital to our day to day survival, it affects feeling, awareness, mood states and consciousness in general. (Go Slow. (C) 2018. Subtle Health, LLC)

If we take a look at the basic anatomy and functions of the different parts of the brain, we can start to get a clearer picture of what happens when we’re affected by the symptoms of a traumatic experience. The brain consists of three major pieces or areas: the forebrain or neocortex makes up the majority of our brain’s mass. When we imagine the brain with its two hemispheres of gray, wrinkled matter we’re imagining the forebrain or neocortex. In the middle and inside space between the two hemispheres is the mid-brain, also referred to as the limbic system. The back area of the brain and brain stem or cerebellum comprise what is sometimes referred to as the “lizard brain.” Our prefrontal or neocortex is largely responsible for our “thinking” or intellectual, reasoning, decision making capacities. Our middle brains help shape mood, memory and emotion. Any external input, experience or stressor meets this area of the brain first before the other two parts of the brain perform their functions. The hind brain is responsible for instinctive reaction. When we need to respond to an external stressor quickly, when we have to fight or flee or freeze without “thinking,” we have activated the hind brain.

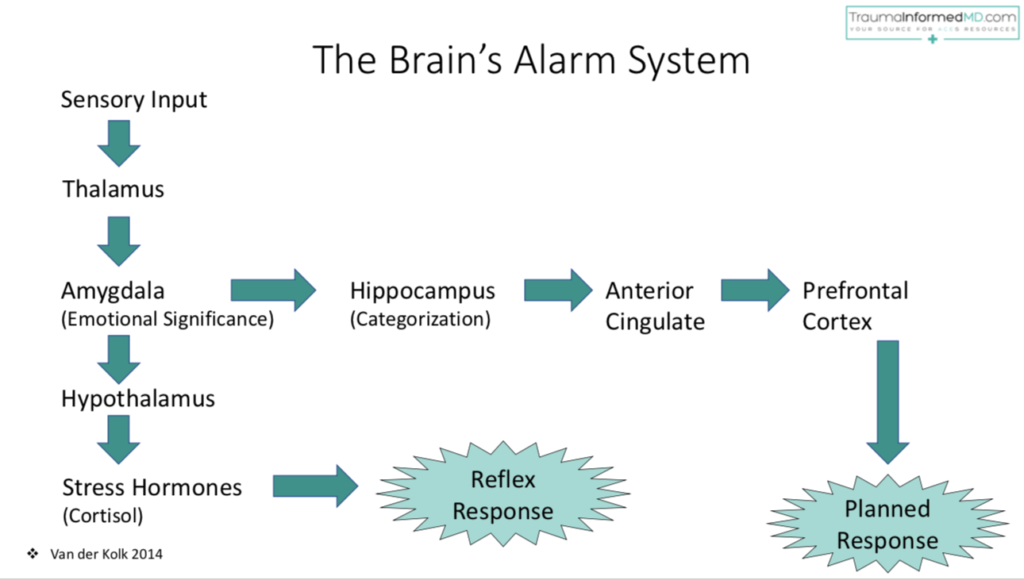

In the diagram above, sensory input arrives at the thalamus and amygdala and then takes one of two divergent paths. The thalamus is the “information relay” system for incoming sensory experiences, and also plays some role in sleep, wakefulness, memory, learning and consciousness. The amygdala regulates fearful or threatening stimuli, and assigns emotional resonance to memories. The hippocampus is responsible for storing and categorizing memories, including memories of stressful or traumatic events. We need memories of such events in order to determine if they are threatening to our survival if and when the re-occur.

Traumatic events often require a “reflex” response, activating the hind brain. Stressors that aren’t life-threatening however, can be processed through the alternate route, where the anterior cingulate and the prefrontal cortex can plan a more “rational” response. Recurring traumatic experiences, or unprocessed trauma that results in PTSD tends to shut down this response route. The brain and nervous system get “stuck” in the fear inducing response that activates the SNS. When the body and nervous system are stuck in this cycle, they’re telling the brain to continue to produce the stress hormone cortisol, so we end up constantly “up-regulated.”

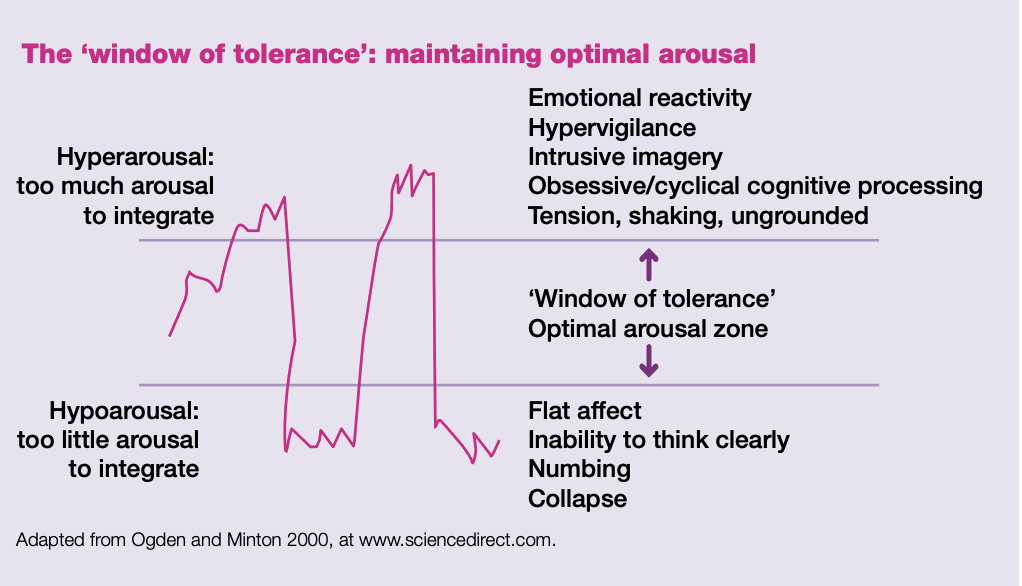

There is a “window of tolerance” within which our nervous system functions optimally, where the delicate balance that is homeostasis occurs. We react to stress and also “down regulate” within this window. When we are stressed, or traumatized to the point of hyper- or hypoarousal, we are not integrating the emotional effects of the experience and will shut off our normal routes of memory recall and reasoned response mechanisms.

With PTSD, certain “triggers” can activate the “fight, flight or freeze” response. When we’re triggered, it’s as if we are experiencing the traumatic event for the first time. Touch and sound, even smells and taste can all be sensory triggers, and when our systems are “primed” for them or in a state of hyperarousal, we’re in a state of constant, anxious vigilance. The opposite can also be true, where we remain in a flat, numbed state of hypoarousal.

This “stuck” cycle doesn’t allow the body and brain to process and integrate the experience. Yoga helps to get this cycle “un-stuck,” clearing the pathway again for a more measured response to stimuli, and a widening of our window of tolerance.

How Yoga Works: Breath, Embodiment, Unity

Consider your capacity as a yoga practitioner or teacher to observe your breath. Simple, right? You might try, as a brief exercise, to watch your breath for five or ten cycles right now. Or to place awareness on or in a specific part of your body. Or, to coordinate movement and breathing, by raising your arms as you inhale, and lowering your arms as you exhale. As yoga practitioners, these inquiries are second nature to us. Now briefly consider not being able to do this, or consider being seriously challenged by the instructions and then the task (and at how frustrated you might feel at the discovery that something so seemingly simple is not that simple).

Trauma and PTSD create a field of disassociation between body and mind. We can think of breath as a link between the two. When we can identify breath and then learn to lengthen it or pause it, to change its various qualities, we can access our body’s natural de-stressing response. Studies of the breath and respiration indicate that a longer exhalation is key for this activation to happen. In fact, the longer exhalation stimulates the vagus nerve to activate your PNS.

Specific breathing or pranayama techniques are not as important as knowing how breathing directs our nervous system to down-regulate (remembering too, that someone in a hypo-aroused state might benefit from a technique that would stimulate or up-regulate the nervous system rather to calm it down even more).

Breath as a tool for trauma also anchors us in the present, something that for trauma survivors is often elusive – flashbacks, unwanted memories and rumination often keep them mired in the past, or worrying about future traumatic experiences.

When we are able to ground our attention in something as present as this breath, and the next breath, we become aware of how breath is embodied. We can get curious, exploratory. How does breath feel in the abdomen? In the chest? In the face? How does inhaling feel, compared with exhaling? Is there a pause? Is the pause a comfortable one? And so on. Practicing this way reminds us of who we are as embodied beings. Proprioception and interoception – knowing where you are in space and in relation to other people, and the ability to sense internally – are faculties many people will never know have names, although they’re subconsciously executing them in some way all the time. As yoga practitioners, we consciously fine tune these abilities to gain a deeper sense of our reactivity and response to the situations life presents to us daily.

Trauma and PTSD separate us from ourselves and from these capacities. When we work with people who’ve experienced trauma, we are helping guide them toward learning or re-learning these skills. To be able to respond skillfully, rather than react instinctively, is to re-establish the mid-brain/fore-brain connection.

Processing the emotions and the experience of a traumatic event takes time and practice. Yoga can help by allowing us to slow down, to make time and space to acknowledge or witness feeling states without getting “caught” in the web of reactivity. We practice presence by cultivating our “witness mind,” an orientation that opens awareness to how we feel and respond in the “now” rather than in the past of the traumatic event. Yoga deepens the mind-body connection.

Yoga also trains us to sit with discomfort, tension and effort. We learn our limitations – of strength, balance and mobility. How long can we hold that discomfort and maintain our equilibrium? Yoga teaches us how to “bear up” under the work of a posture, a lesson we take from the mat into the world. For trauma survivors, learning to be with the discomfort of a pose can translate to difficult emotions and memories, and so can be part of a wider protocol of healing.

Finally, in the integration of mind, body and breath, yoga allows us to recognize our inherent wholeness. As my Warrior Spirit Project friends remind us, “You are not broken. You are whole.” And that while we are discrete, embodied beings, we also share a relational field; we are not alone in suffering. The yoga class is a container that can foster safe community among those with shared traumatic experiences.

Teaching Trauma Informed Yoga

This article should not take the place of actual trauma-informed yoga teacher training. A quick Google search will bring up many resources when you’re ready to pursue additional training. Below are some guidelines on how you’ll create that container and teach trauma-sensitive yoga.

Your approach. A simple, pared down style of teaching works best. Be welcoming, adaptive and accommodating. Go slower than you think need to. Be gentle but direct in your tone. A simplified approach isn’t flowery or big on metaphors in your speech or cueing. Typically avoid using Sanskrit, at least until you’re on familiar ground with your students and there’s openness and curiosity around language. But do invite curiosity around feeling and sensing and dispense with “telling” people what to feel. Use more “could you”s and fewer “you should”s.

One verbal cue that is especially challenging to let go of is “relax.” Cueing people to relax is telling them what and how to feel, and trauma survivors, who tend to remain fairly unrelaxed, need more guidance on how to get there, and to know it’s okay if they don’t.

Keep your language at the forefront of your teaching persona and cue more frequently. Long silences can leave students “un-moored,” so keep drawing students back to themselves, the room, the pose, their body, breath and the moment using your voice.

Extras. Sensorially speaking, again simple is better. So re-think the use of incense, candles and music. We’re trying to create an environment that considers anything that could be a possible trigger for someone who’s experienced trauma. Someone who was sexually abused might be triggered by a particular scent, or by body-conscious clothes. Someone who’s trauma centered around military combat might associate exotic sounding music with their traumatic experience. Clothing and jewelry with spiritually ambiguous iconography is also a potential reminder of wartime experience. Do your best to de-mystify your classroom.

Props. Should you use or not use props? It depends. A restorative class that uses a maximum of props might be overwhelming to trauma survivors. Getting everything “just right” might be given more priority than getting the optimum experience from a restorative pose. Props in a more standard “hatha” class can sometimes send the message that the student isn’t “good enough” to do a pose without a prop. We’ve all been there as beginner students. If you as the teacher are modeling poses with props, perhaps demonstrating your own “limitations” and how a prop can allow for a more stable or open experience of a pose, then go for it. On the other hand, think about how a yoga strap might be triggering to someone whose traumatic experience involved being bound or tied up. Teaching a class without props is about more simplicity, less complexity and fewer risks of triggers.

Assists: model, verbal, physical. Speaking of modeling, as a general rule, the more you can be the example of what you’re teaching the better. As much as possible, model the pose you’re trying to teach or the movement you’re trying guide students to experience. The less you’re moving around, too, the more you establish yourself as a stable presence in the room. Lots of verbal cueing that is slow, precise and intentional works well.

Physical assists are a sensitive arena, in any class. Giving your students the power to ask for an assist, or to give you their permission to be touched is paramount today. This dynamic is especially important in trauma informed classes.

You might dispense with physical assists altogether in the beginning, until you establish a good rapport with your group. Always ask permission and remain vigilant around the specific assist you want to offer. What might not be triggering to one student, could very well trigger the person on the next mat! So it’s always, always imperative to explain what you want to do and why you want to do it, before you do it.

Environment: windows, doors, lights. As important as all of the above, is the physical space you and your students use. Having your eyes open during your class and having clearly marked exits are key to remaining fully aware of what’s happening with your students in their experience of your class. If a student becomes triggered and needs to leave, ensure that door is easily accessible. Situate yourself nearest the door, with your back to it, so students have a clear view of it. Keep the room well-lit, erring on the side of more light if you have control of the lighting. Windows should allow for class privacy, so adjust blinds to prevent your class from being a “fishbowl” to outside foot or car traffic. Create an environment of safety given whatever parameters you have to work within. And going back to language and cueing, it’s helpful to announce the fact that your eyes will be open during the class (while stating they are free to close theirs or leave them open) as well as changes to the environment so that students aren’t startled when doors close or lights come up or down. Even sounds outside the room that are out your control can be explained or commented on, maintaining the space of the classroom as safe and contained.

In today’s world, all yoga should be trauma-sensitive. We should approach every class we teach with the understanding that at least one person has been through something that continues to affect them emotionally and psychosomatically. Whether you’re working with trauma survivors or not, enter every class respectful of your students’ life experiences, and with the assumption that there is more to them than meets your eye. Honor their capacity for healing, for deepening their own knowledge and experience of self.

Resources

If you think you’d like to work with veterans and the military community, DFW-based Warrior Spirit Project, Warriors at Ease or Veterans Yoga Project are good organizations to contact for training.

Those organizations can then help you find opportunities to teach through mental health facilities, the VA or a local Vet Center. Substance abuse treatment clinics, correctional facilities, homeless shelters and organizations that treat trauma or support victims of domestic abuse are also places that benefit from skillful, trauma-informed yoga classes.

Books and Trainings

Blackaby, Peter. Intelligent Yoga

Blackstone, Judith. Trauma and the Unbound Body

Conger, John P. The Body in Recovery: Somatic Psychotherapy and the Self

Cope, Stephen. Yoga and the Quest for the True Self

Criswell, Eleanor. How Yoga Works: And Introduction to Somatic Yoga

Emerson, David & E. Hopper, PhD. Overcoming Trauma Through Yoga: Reclaiming Your Body

Harris, Judith. Jung & Yoga: The Psyche-Body Connection

Horton, Carol. Best Practices for Yoga with Veterans

Van der Kolk, Bessel. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and Body in the Healing of Trauma

I’m listing the various trainings I’ve pursued simply as an example of how I built my own base of knowledge and application. There are many, many routes this could take, based on your own goals and interests:

Applied Psychology for Yogis, Livia Shapiro, MA, Ecstatic Unfoldment

Amy Jones, LPC-S, RYT

Sacred Centers: Psychology of the Chakras, Anodea Judith

Mindful Trauma Oriented Yoga – Tzivia Stein-Barrett, CP, LCSW, ERYT

Warriors at Ease Level 1 Teacher Training

The Yoga and Neuroscience Connection – Subtle Health, Kristene Weber, MA, C-iAYT, RYT