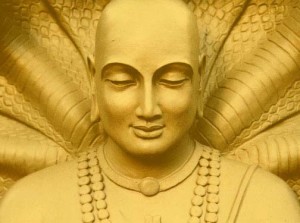

The sage Patanjali, author of the Yoga Sutras

Modern postural yoga is but one aspect of a total system of self understanding and self-compassion.

While also the name for a certain style of modern postural yoga (to confuse things up a little bit), known for its demanding vinyasa and increasingly challenging sequences of poses, ashtanga also refers to a system of psycho-spiritual discipline that includes postures as only one of eight different practices aimed at opening the practitioner to increasingly deeper levels of self awareness (or higher levels of consciousness, if you prefer. Do you ascend, or do you descend? Question for another post…).

The eight “limbs” begin with 10 observances, sometimes likened to “commandments,” although there is a hint of the punitive in commandments that doesn’t really come into practice with the eight limbs. To me, they are more closely aligned with the Buddhist Eight-Fold Path, both in spirit and in history. These ten observances are split evenly between the “yamas” and the “niyamas” and proscribe conscious attitudes toward others and toward yourself.

Let’s content ourselves today with a brief description of the first limb, the “yamas.” Iyengar describes the yamas as

“rules of morality for society and the individual, which if not obeyed bring chaos, violence, untruth, stealing, dissipation and covetousness. The roots of these evils are the emotions of greed, desire, and attachment, which may be mild, medium or excessive. The only bring pain and ignorance. Patanjali strikes at the root of these evils by changing the direction of one’s thinking along the five principles of yama.”

So, you might guess correctly that the yamas are defined as the opposite of these characteristics and emotions. Chip Hartranft in The Yoga-Sutra of Patanjali suggests that rather than following the yamas as “commandments” (even Iyengar uses the term as a way of promoting necessary discipline), that we think of them as “skillful ways to relate to the world without adding to its suffering or ours.”

- Ahimsa – non-violence. In Light on Yoga, Iyengar spends more time discussing ahimsa than any of the other yamas. He reminds us to see ahimsa not simply as an edict not to harm or to kill, but to reorient ourselves to an attitude of love and reverence for life. In addition, because violence stems from fear, anger and ignorance, when we change these attitudes and live in service to the myriad forms of life around us, we are free. We can then for example, oppose wrong-doing in others and still love them. Hartranft translates the specific sutra pertaining to ahimsa: “Being firmly grounded in nonviolence creates an atmosphere in which others can let go of their hostility.” (34). Like begets like. (Or, how likely is someone to mess with you when they understand you’re not a threat?) Being grounded in non-violence has the ripple effect of allowing others to “stand down,” let go of fear and hostility, and open to love.

- Satya – truthfulness. And speaking your own truth, so resisting the impulse to stay silent when your words are needed to safeguard or emancipate others. Satya also drills down to specific kinds of speech to avoid: abuse and obscenity, lies, gossip and the ridicule of others’ beliefs. Again, Hartranft suggests the edict to truthfulness has a reflective quality to it: “…one’s truthfulness toward self and others not only ennobles one’s personal actions but also removes the pressure to deceive that those around us may feel.”

- Asteya – non-stealing. Again, there is not only a literal admonishment not to take what doesn’t belong to you, but to ripple this out to consider any and all ways we might be “taking” from others, and even from ourselves. Iyengar suggests “misappropriation, breach of trust, mismanagement and misuse” all stem from the impulse to “take,” an impulse that arises out of craving. The practice of non-attachment to material things, only procuring the minimum of resources necessary for a purposeful or devoted life re-wires the mind to “relax in the world as it is” (Hartranft, 34).

- Brahmacharya – self-restraint. Iyengar calls this yama “the battery that sparks the torch of wisdom” (35). There are two primary ways to consider brahmacharya: as an ascetic or renunciate; so withholding oneself from congress with the everyday world, to include more specifically, sexual congress. If we consider sexual energy symbolically, as life force, creative energy, something powerfully potent, then harnessing that energy, redirecting it to spiritual practice can only deepen one’s devotion, move one toward higher consciousness. Iyengar too allows for an interpretation of self-restraint that applies to us, to marrieds and “householders.” Living in the world of work, family and society without attachment to its fruits, and consciously re-directing that outward expenditure of energy inward is ethical self-restraint.

- Aparigraha – non-grasping. Or “Freedom from the compulsion to have” as Hartranft puts it. Similar in thought to the practice of asteya or non-stealing, aparigraha is a conscious movement toward living simply, with only what is required, acknowledging the empty value of things in themselves. Hoarding and collecting are symptoms of a mindset that hasn’t yet allowed for the faith we have within us everything we need for “fulfillment.” When we can see our wholeness and completeness within, we will stop reaching outward for things we don’t need.

The yamas are again, ways of interacting with the outer world. The niyamas will help guide and structure our inner states, our self-care. More on the niyamas in the next post…